The idea of sustainability is a two-fold goal for climate-conscious businesses that have made addressing our climate crisis their mission. Because no matter how noble it is to develop an environmentally sustainable product or solution, if a company cannot find its footing and sustain operations, it will never achieve the impact it is striving for.

Many innovators enter the climate space because they believe it’s a way to apply their skills toward a greater, global imperative. But if the company they found or joined is too broadly focused or hasn’t articulated a clear problem to solve, success will be dispersed across what each individual believes it needs to look like.

So, despite everyone being well-intentioned, this misalignment will strain a company that’s fledgeling, both disappointing and disillusioning the altruistic people drawn to work in the climate sector.

Building “Capital I” Impact

Many years ago, while helping launch Civic-Tech Toronto, a community that tackles civic challenges through technology, design, and other innovative means, I was introduced to the Theory of Change.

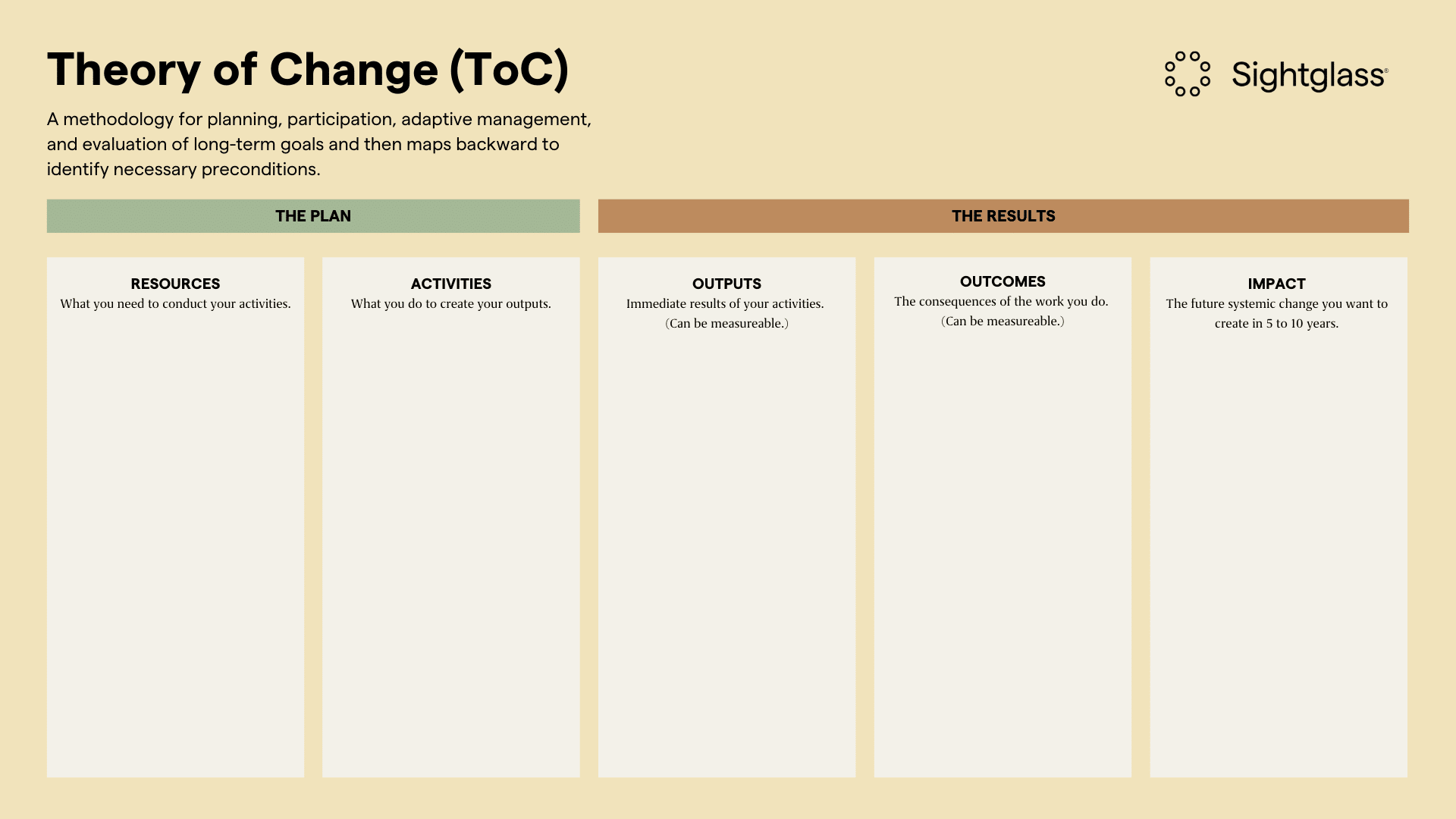

Originating from the not-for-profit space and designed to align resources and activities to their desired impact, the Theory of Change starts by defining the “Impact” an organization wants to see in the world. From there, the model works its way backwards to outline how Impact is delivered – ie. how the organization achieves change in the world.

The Theory of Change is divided into two sections: the Results and the Plan. The Results section includes three groups, which we work our way through backwards:

- Impact: The future systemic change you want to create five to ten years out.

- Outcomes: The consequences of the work you do. This can be measurable or not.

- Outputs: The immediate results of the activities you conduct. Again, this can be measurable or not.

Once the team has completed the Results section, the Plan section focuses on two groups:

- Activities: What do you do to create your outputs?

- Resources: What do you need to conduct your activities?

Because the Theory of Change provides focus on the company’s Impact as well as what it takes to get there, the team has clarity on how everything they do works toward the desired change.

While this may look like an operational view of the business, there are clear product implications embedded in the Theory of Change, especially in terms of how the solution delivers impact. In a sense, the Theory of Change articulates why a particular product or service needs to exist.

How prioritizing operational sustainability promotes environmental sustainability

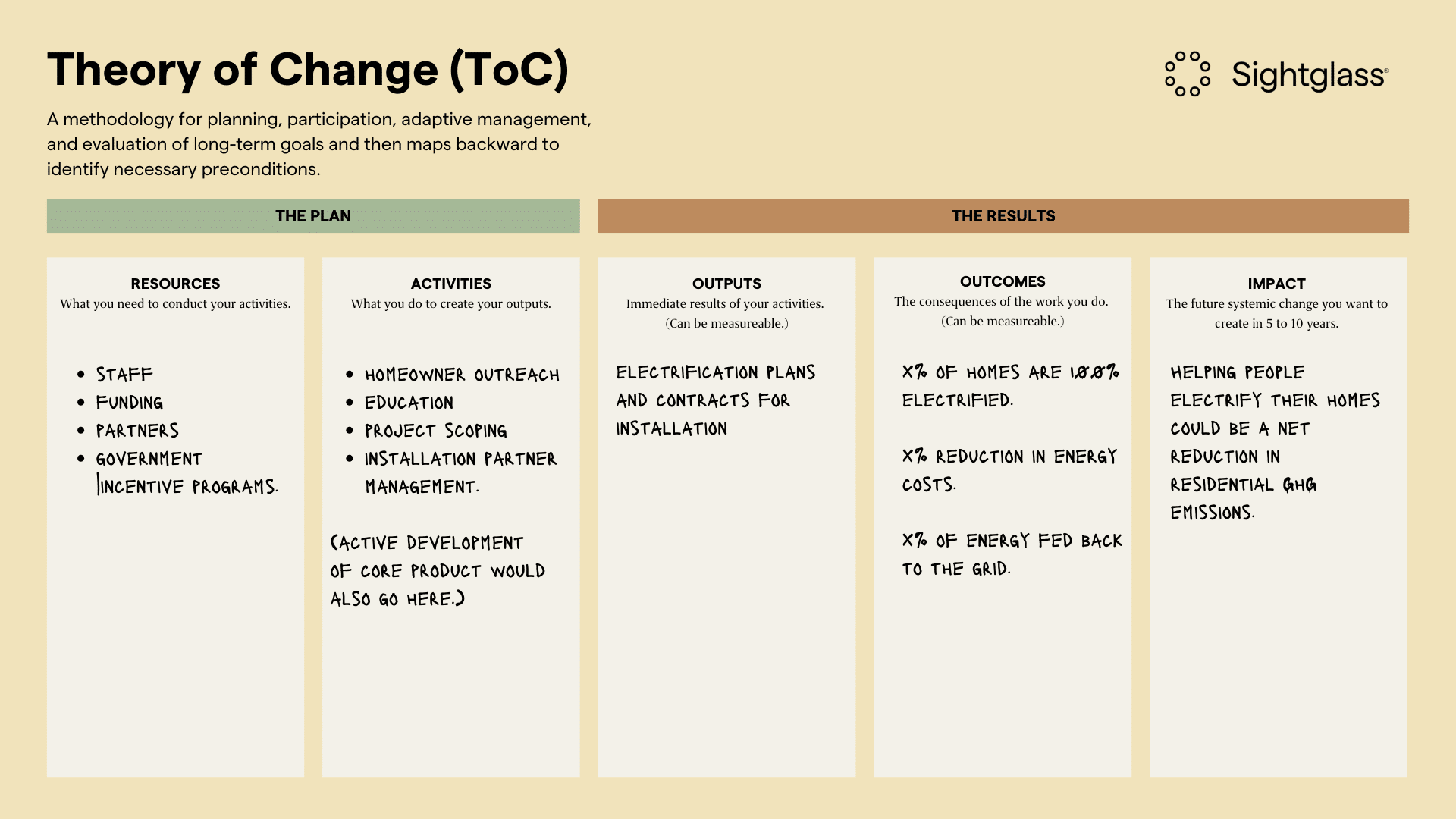

To illustrate, let’s apply the Theory of Change to a company that facilitates solar adoption by advising homeowners and connecting them to installation partners.

For the Results section:

- Impact: Helping people electrify their homes could be a net reduction in residential GhG emissions.

- Outcomes: All those electrified homes in the world could be summarized as follows:

- X% of homes are 100% electrified.

- X% reduction in energy costs.

- X% of energy fed back to the grid.

- Outputs: We could define this as electrification plans and contracts for installation.

For the Plan section:

- Activities: This could range from homeowner outreach, education, project scoping, and installation partner management. If that’s all facilitated by a SaaS-like software solution, then active development of the core product would go here.

- Resources: This might be the company’s staff, funding, and partners — perhaps even government incentive programs.

When looked at from left to right, from Resources to Impact, it becomes clear for anyone inside the company how their activities will impact the stated goal of reducing residential greenhouse gas (GhG) emissions.

Now that the company is better aligned with how it creates Impact, the next step is to determine how valuable that Impact is and whether (or not) it can become a sustainable business.

When we conduct Growth Mapping for a client, we’ll often lead a Theory of Change or Business Model Canvas workshop — depending on how well the team is aligned on its Impact. If alignment is strong, a Business Model Canvas workshop grounds the stated Impact in the practical realities of sustaining a business.

If the company is struggling to articulate the change they are striving to bring to the world, if the mission and vision are too broad and difficult to action, then a Theory of Change is the ideal tool for bringing everyone into alignment on why the company exists and how everyone at the company collectively contributes to the Impact sought.

Following up a Theory of Change workshop with a rough revenue model that puts some numbers to the opportunity before the company is important. While a Theory of Change can help ensure the company can solve the identified problem and create Impact, none of that matters unless the market sees the problem as worth solving.

A revenue model includes assumptions about total market size, pricing, and number of customers required to achieve X% share. It is important to understand the unit economics of the business because that affects the product and organizational design.

How many times have you heard someone naively say a market is worth $100B and that if “we can achieve just 1% market share, it will be worth $1B!”

What is overlooked in such opportunity-sizing exercises is a breakdown of how many customers are required to achieve a 1% share. Is it ten large clients? Or 10,000 small ones? Is the government involved in creating incentives for those markets? How do those impact pricing and sales? What is the nature of the customer relationship? Transactional? Consultative? Long-term? Many of these answers can be pulled from a Theory of Change — or a Business Model Canvas, but putting numbers to them will help ground the reality of establishing a sustainable business.

If climate innovators can achieve that foundational sustainability, then the likelihood of making an impact on our planet’s sustainability increases exponentially.